Intent HQ Validated as Built On Databricks Partner

Intent HQ enhances AI capabilities and accelerates innovation through Databricks partnership, enabling robust, scalable data solutions for customer engagement.

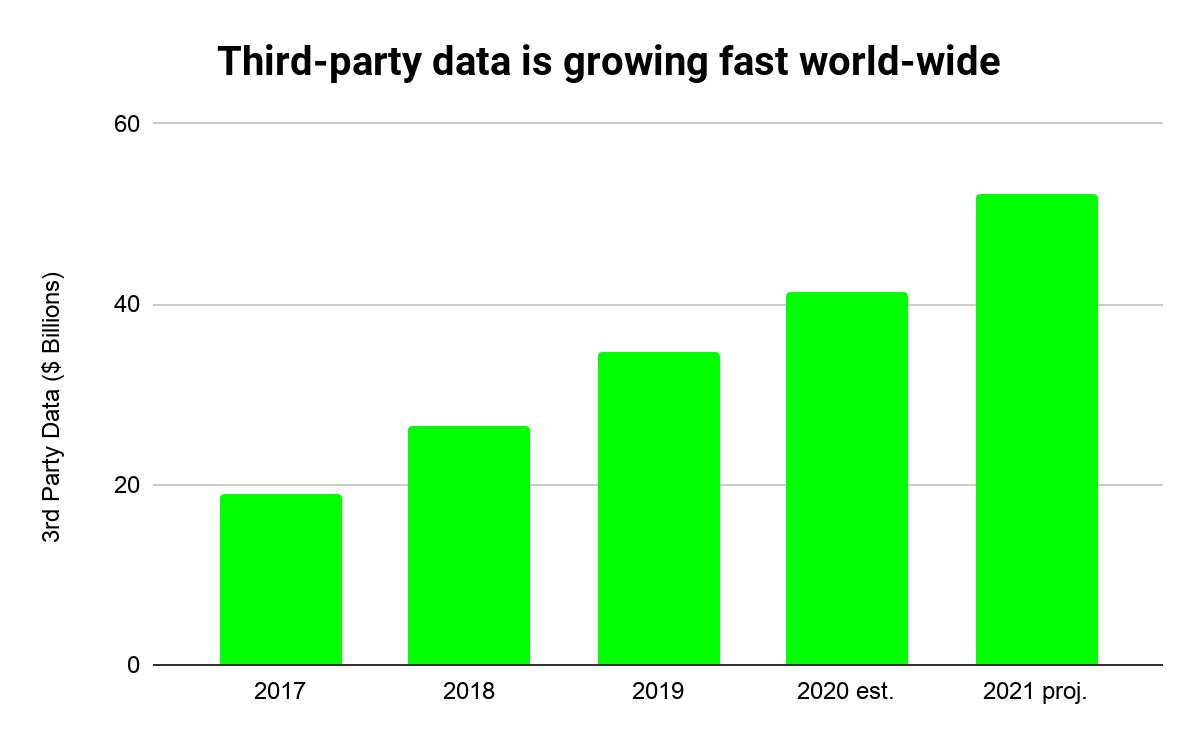

It was expected to die. Instead, it continues to grow.

Despite the rise of GDPR and other privacy regulations, marketing demand for third-party data has continued to drive billions of dollars of double-digit growth. Now, predictions of its impending demise have surfaced again.

According to OnAudience, a provider of third-party data, Europe accounts for $6.3B of the estimated $41.4B global market in 2020. They project European sales will grow at 22% in 2021, to $7.6B. The UK is estimated at $3.1B this past year, $3.6B in 2021. Although smaller, double-digit growth is expected in France and Germany. OnAudience attributes sales mainly to the growth in digital advertising, which was boosted by the pandemic even as overall advertising shrank in 2020.

One way to categorize data is by its source.

First-party data is “your own company’s data.” Most of this comes from your website, CRM, order information, and surveys. For companies providing digital and communications services to customers, it includes data from operational systems such as network data. A sub-category of first-party data is “zero party” data, information knowingly submitted by a customer in a form or survey. In many contexts first party data is the most valuable kind, because it reflects your relationship with a customer. It offers a greater possibility of “opting in” customers for marketing uses of the data and of handling it in a privacy-safe way. Importantly, the accuracy and timeliness of first party data can be managed for high quality.

Second-party data is someone else’s data, where you know who that provider is and can know something about its quality. It can extend the reach of your marketing efforts beyond your current customer base, and expand your knowledge of current customers. However, effort is required to use data from other firms, even those with whom you already do co-branding. In addition to the need for a data sharing arrangement, requirements under privacy laws like GDPR or CPRA can pose legal risks and operational challenges.

Third-party data is also someone else’s data but is compiled by a service provider. The original sources of specific data are generally not well known to buyers, so “quality may vary.” Specific targeting categories such as demographics and behaviors may be broadly or inconsistently defined, and individual data elements are frequently blank for many consumers. When inaccuracy causes poor targeting, cost per conversion is higher and consumers are spammed. However, the reach of third-party data today is awesome. Billions of people have been profiled. Other data types just don’t provide this reach, except within the walled gardens like FaceBook and Google. Third-party data can be used to “enrich” your first-party data, and to help you learn more about the anonymous visitors to your website (often as high as 98%). However, a large majority of third-party data sold today is used in support of programmatic advertising. It is this massive use of third-party data which is most under attack by privacy activists

As useful as this data has been for marketing professionals, it is viewed with hostility by many privacy advocates. They say it tramples on personal privacy rights.

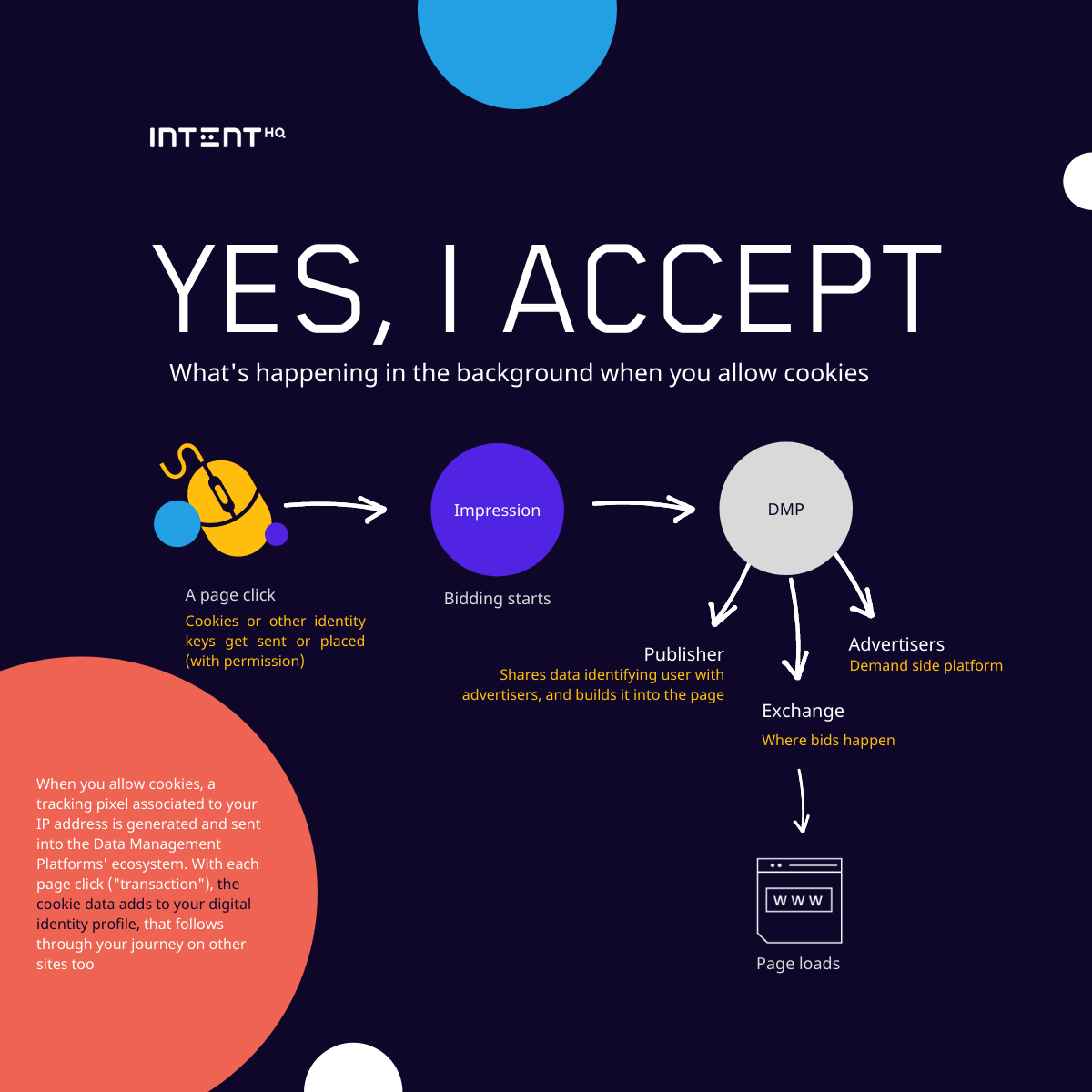

In the EU the GDPR was expected by many to put an end to third-party data. The dominant advertising use case, Real Time Bidding (RTB), was at risk. In RTB, when a consumer clicks on a website and an advertising “impression” is available, advertisers bid to use that impression via automated exchanges. The bidding process takes a fraction of a second. Advertisers will bid higher on an impression with a customer they are targeting, or whose characteristics they are targeting, than on a customer they know nothing about. So, data about each customer is broadly shared for the purpose of boosting the value of each impression. RTB has been good for many publishers, advertisers, data suppliers, exchanges and the other AdTech firms who support RTB. However, RTB has not been good for consumers’ privacy rights.

There is agreement among privacy advocates and regulators that under GDPR, “consent” is the only legitimate way to enable use of people’s information for most marketing purposes. Regulators say a company’s need to make more money isn’t likely to outweigh a person’s privacy interests.

Some in the data industry have acknowledged this. For example, one of the leaders in third party data is Oracle Data Cloud. As reported by AdExchanger in 2019, Oracle Data Cloud SVP and GM Eric Roza said, “Anyone who is relying on legitimate interest to do advertising, audience-based advertising, is putting themselves and their company at risk.”

More recently, the UK regulator Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) all but ruled out anything but “consent” as a legitimate basis for processing personal data. Simon McDougall, the Executive Director of Technology and Innovation said, “…we have reviewed a number of justifications for the use of legitimate interests as the lawful basis for the processing of personal data in RTB. Our current view is that the justification offered by organizations is insufficient.” He added, “We have also seen examples of basic data protection controls around security, data retention and data sharing being insufficient.”

These are the two main objections to the use of third-party data in RTB: consent and security. GDPR’s definition of consent is comprehensive: “Consent of the data subject means any freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous indication of the data subject’s wishes by which he or she, by a statement or by a clear affirmative action, signifies agreement to the processing of personal data relating to him or her.” To privacy proponents, millions of EU residents have not given this comprehensive kind of consent. Under GDPR, consent is not “freely given” if it can’t be just as easily withdrawn. “Opting out” isn’t well implemented in the RTB ecosystem.

GDPR rules require privacy-by-design-and-default, limit corporate transfers of personal data, and mandate data security for personal data. Privacy activist Johnny Ryan, formerly of the browser company Brave (now at the Irish Council for Civil Liberties), called RTB “…the greatest data breach of all time…” because so much personal data is flowing to so many companies with so little control.

In the same January 2020 blog the ICO said, “We will continue to engage with industry where we think engagement will deliver the most effective outcome for data subjects…” and ended its message with: “those who have ignored the window of opportunity to engage and transform must now prepare for the ICO to utilise its wider powers.” In early 2021, more than two and a half years after GDPR became law, neither the ICO nor any other regulator in Europe has decisively moved against the use of third party data in RTB.

Frustrated by the inaction of regulators, the privacy activist community has been filing more lawsuits instead of complaints to regulators. For example, suits were filed in 2020 against Oracle and Salesforce in both the UK and Netherlands. As reported in TechCrunch, the litigants (Dr Rebecca Rumbul, class representative, and The Privacy Collective, respectively) project as much as €10BN in collective claims, if their arguments prevail. Not surprisingly, both Oracle and Salesforce don’t think the activists will prevail, and object strongly to these suits. Lawsuits take years, but the publicity will pressure regulators to move toward imposing penalties.

Now there’s a new challenge to third-party data, one not directly from regulators. The challenge comes from Apple and Google. Some call this “the death of the cookie,” but it is really about third-party data.

Apple’s Safari, and several other browsers with smaller market share including Mozilla’s Firefox, had started to make technical changes to block third-party cookies in 2017. For example, they now prevent third-party cookies from persisting more than 24 hours. In 2020 Google shocked many in the industry when it announced that it will implement something similar by 2022 in its dominant (70% share) browser, Chrome. This “depreciation of third-party cookies” will effectively block the principal way consumers are tracked from one website to another today. The result will also block most of the third-party data used in RTB from being generated. Unfortunately for the industry, Google has been somewhat vague about details of technology and timing. Some in the industry appear to be uncertain, almost paralyzed, as a result.

Moving from the mostly-desktop world of browsers to the mostly-app world of mobile, Apple has announced major changes to how its Identifier for Advertisers (IDFA) can be used by app developers. Essentially, this means that in the future the IDFA may not be used without explicit customer consent. The change is a major step toward “opt-in” consumer data privacy even in places like the U.S. where opt-in consent is not generally required. Apple delayed these changes in 2020 to give the industry more time to adapt but is expected to put it into effect in early 2021. Speculation is about when, not if, Android will follow Apple’s move toward consumer privacy.

Consumers are not expected to opt-in to much of this tracking by mobile apps. Combined with the depreciation of third-party cookies, these changes could shut down as much as 90% of current third-party data sources. Critics say these changes may be good for consumer privacy but they also benefit Google and Apple. Facebook has complained the changes are bad for small businesses. It appears that consumer privacy and the desire to rein in “big tech” are in conflict. No doubt this is a reason regulators are moving slowly.

Nobody seems quite sure what comes next. But a few trends are evident.

Contextual Advertising

One group of publishers, including the New York Times (NYT), is aggressively changing its advertising-sales model to feature “contextual targeting.” This is a back-to-the-future way for advertisers to target based on customer interests. Note that “contextual” can be compatible with RTB, but without the need for third-party customer data. For example, a repeat reader of the Travel section of the NYT is an excellent candidate for travel and lodging advertisers… and there is promise of more precision about customer context in the future. One advantage to publishers of this “contextual” approach is cutting out some middlemen and getting more of the advertiser’s dollar. It is a great example of publishers using their first-party data. Cheered along by privacy advocates like Johnny Ryan, some publishers are reporting higher net revenues using a “contextual” approach. However, it is not clear “contextual” can work for smaller publishers.

The data and Ad-tech communities are not surrendering to these challenges. There are dozens of new “universal customer identifier” and “identity graph” schemes under development and many already launched. These attempt to replace the cookie and may keep RTB alive much as it is today. Adweek reports some are already gaining traction. Especially if these become interoperable, they may be the new way that consumers are tracked. However, in the context of GDPR and probably California’s new CPRA, the legal status of these alternative identifiers is unclear. Consent may still be required, or an opportunity to opt out. Much will depend on whether and how regulators actually take action, or if the courts get involved.

Meanwhile for most marketers first-party data is gaining in importance. As a result, major ad-tech and MarTech firms such as Dentsu Aegis have been beefing up their capabilities to support more use of first-party data. The value, accuracy and timeliness of first party data will remain while third-party data becomes less certain.

It is hard to believe that RTB is a fairly recent development, in use for just over 10 years. Now because of the growing revolt of customers against the privacy problems associated with RTB and third-party data, as well as the regulations this has encouraged, we are probably looking at another decade of rapid evolution in marketing technology. However that turns out technically, “opting in” customers for marketing uses of first-party data will play a major role. The strong context and data quality offered by first-party data, featuring customer relationships, will remain the best way forward for personalized marketing.