Customer analytics in telecoms: Why it matters

The telecoms industry holds some of the most extensive and detailed customer data of any sector. One major advantage for these firms is that the data they possess comes directly from their customers.

Are you a troubled developer because your boss heard about BigData and is asking you about it? Are you a CEO who just wants an understandable explanation about the CAP theorem? Are you the partner of a developer who just wants to understand what he/she is doing?

Don’t worry, we have the solution: BigData and the CAP theorem explained in plain english.

Sometimes we (techies) tend to talk techie and not care about the real world understanding what we are doing. In my particular case, my wife often asks me about my day over dinner; I have to admit that explaining it in plain (in my case) catalan can be quite challenging.

This article will pick some ideas from those conversations and will try to explain, by means of a metaphor, the implications of Big Data and the CAP theorem.

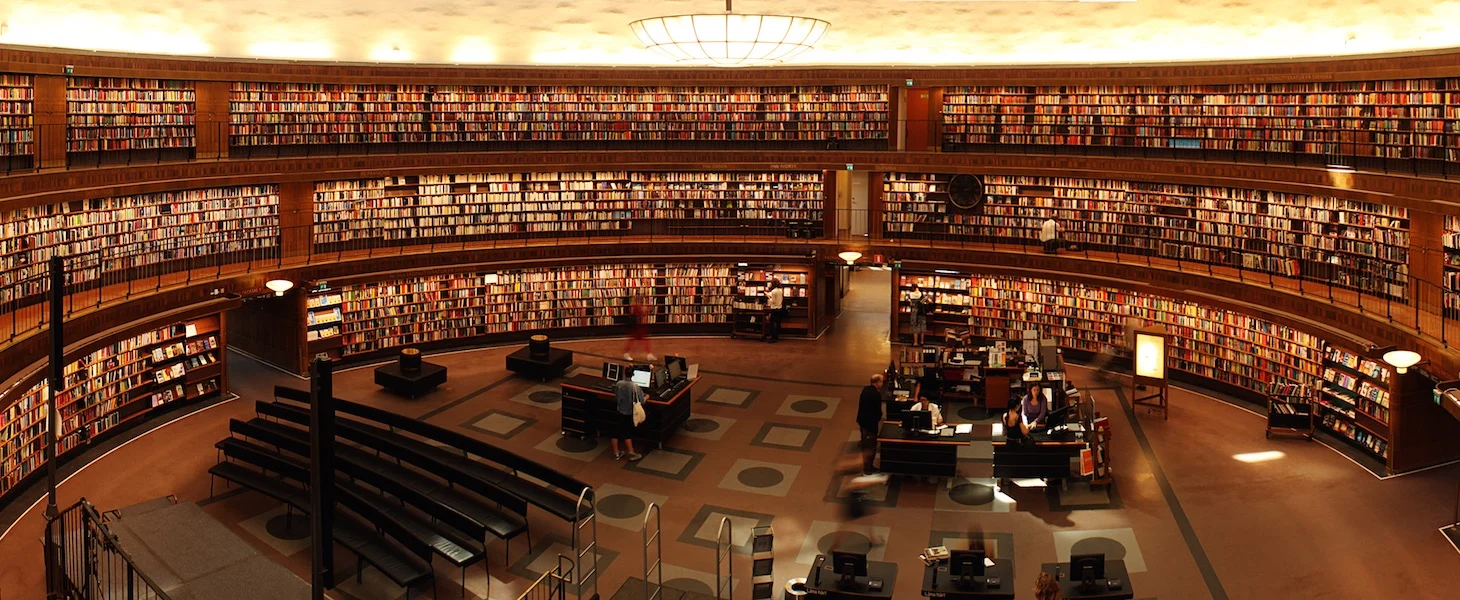

Imagine that you own a library (yes, that will be our metaphor). You have lots of books and magazines in it but, at some point, you don’t have enough space in the shelves, so you decide to buy some more.

After some weeks, you’ve filled the five floors of your library with shelves but you still don’t have enough space (disk) for all the books you want to keep. This is when you decide you need to add floors to the library building.

With more books you also need to grow your library index, so you need to buy more cards (memory). You’ll probably need to hire more librarians (cpu). Also, there is a point where there are queues outside the building (too many visitors) so you need to open more entrance doors (network).

As you have imagined, this is what is called “scaling up” or “scaling vertically”. You find your bottleneck (e.g. memory) and just make it bigger.

Someday you’ll see that the cost of expanding your library is prohibitive or that it is physically impossible to add more shelves, indexes or doors. That day is the day you realise you need to build another library.

And yes, your guess is correct, creating a library network and adding more nodes (buildings) to it would be to “scale out” or “scale horizontally” your library.

Now that you have multiple buildings you need to make some important decisions. The first one is to decide how to distribute your books among the different libraries (sharding).

One possible and easy solution would be to distribute them by author. Books of authors whose surname starts with A, B, C or D go to building number 1. Authors with surname starting with E, F, G or H go to building number 2 and so on.

You soon realise a problem with that approach. The authors surnames are not distributed equally and some authors (like Terry Pratchett) have written many more books than others. The implication is that some of your buildings are half empty while some others are too busy.

You need to choose a better criterion (partition or shard key) that is easy to compute and well distributed. There are several options and there is not a good answer that will work in any scenario (it will depend on how your index is created, what queries can you do, what are the most common queries people is doing…). However, as an example, hashing the book title and using the modulus to decide which building the book is in would provide a better distribution of the books.

One day you read about what happened to the alexandrians and think about what would happen if one of the buildings catches fire. So you decide to buy extra copies of your books and put them in different buildings (redundancy).

Of course, this comes with a cost and implications, both of them will depend on how many copies you want to keep (replication factor) among others.

Besides the obvious advantage of having backup copies of each book (you could have achieved that by simply having a warehouse), this new architecture has a major drawback: every time you receive a new edition of a book, you’ll need to send the updated copy to each of the buildings with a van, a truck, a train or a bicycle (unfortunately, books don’t yet send themselves!)

Once you have several buildings spread all over the city with the books distributed among them, you normally find this is when you start having troubles.

Let’s see what are the problems that arise when you distribute your data by looking at different scenarios but, before that, we will define three desirable conditions that any library should fulfill.

This is called the CAP theorem. Eric Brewer stated that it is impossible for a distributed computer system library to be consistent, available and tolerant to network road partitions at the same time. The concept that you have to choose “two out of three” was rapidly spread, although, as we’ll see next, it can be misleading.

As just mentioned, many people saw the CAP theorem as a simplification that stated that you had to choose between a system being CA, CP or AP, which was kind of misleading as the same Eric pointed out some years later.

In a distributed system (like our library) you will almost always rely on something you don’t own or control, the communications. That means that you system willhave network partitions.

In our example, you can’t rely on the roads being always open, as it may snow, there may be a parade or a demonstration that doesn’t allow you do go from one library to another.

In the real world, if your system is in two different data-centers you must account for the likelihood of a network partition. The probability of a network problem is much lower if your entire system is in the same datacenter and you control it, but it’s not impossible.

The conclusion that comes from all the above is simple. If you want your libraries to be tolerant of not being able to communicate with each other, you’ll need to plan what to do in case of a network problem:

This is (again) a bit misleading as your system doesn’t need to choose between being consistent or available and the approach taken by most modern solutions is to have a balance between consistency and availability. However that’s probably a discussion for another post, this one is already too long.

Library picture by Tamás Mészáros is licensed under CC0 1.0